Rosa wichurana |

|

| Foto di A. Barra - tratta da Wikipedia |

Sometime in the early twentieth century a rose seed germinated in the care of a skilled hybridist who was a leader in using the then relatively new Rosa wichurana (or as it was known back then, Rosa wichuraiana). The seedling grew and made its very excellent qualities known: and before long it entered commerce with the name of the hybridizer, the 'Dr. W. Van Fleet' rose. It's a huge shrub rose with one season of profuse bloom; the silvery pink flowers have the green apple scent characteristic of so many wichurana hybrids. The rose ‘Dr. Van Fleet' proved to be enormously popular, and was soon being propagated in numbers by many nurseries.

|

| Rosa 'New Dawn' tratta dal catalogo di Anna Peyron |

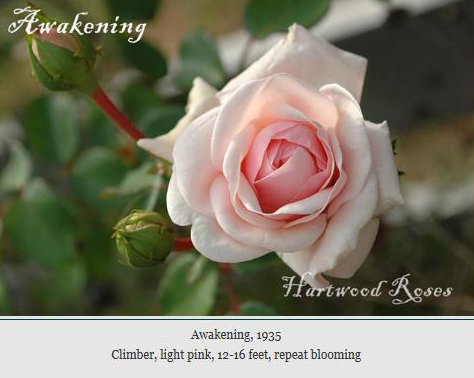

Sometime in the late 1920's the stock of one nurseryman began to show a surprising and delightful characteristic: it rebloomed throughout the summer. These reblooming branches were themselves propagated. When it became apparent that the rebloom was a reliable characteristic, these reblooming plants were renamed 'New Dawn'. It was introduced in 1930 and has the distinction of having been awarded the first plant patent in the United States. To this day 'New Dawn' is widely held in high regard. For purposes of this discussion, keep in mind that 'New Dawn' is an outgrowth of that original seedling. 'New Dawn' became even more popular than 'Dr. W. Van Fleet', and it too underwent extensive vegetative propagation. In the 1930's a keen eyed Czech nurseryman noticed that one of his plants produced branches with very double flowers, flowers which had more petals than the typical 'New Dawn'. These branches with very double flowers were propagated. When it became apparent that the extra doubleness was a fixed characteristic, the plants grown from these branches were named 'Awakening'. That's what you see in the image hereafter.

|

The three roses 'Dr. Van Fleet', 'New Dawn' and 'Awakening' form a single variable clone. Perhaps you're wondering “How can that be, they are not exactly alike, and aren't clones exactly alike, isn't that what the word ‘clone' means?” No , that's not what it means. The word clone (in the plant science sense) was first used in the offices of the Department of Agriculture. One of the researchers was searching for a word to describe the group (note that, the group, not the separate plants) which arises when a plant is vegetatively propagated. One of his co-workers who knew Classical Greek suggested the Greek word for 'branch'. In a conventional transliteration from the Greek alphabet to the Roman alphabet, this would be written 'clon'.

Those who knew Classical Greek knew that the “o” was a long “o”. But this spelling ran afoul of the bizarre rules of spelling we have in English: most native speakers of English who did not know Classical Greek pronounced the word the way it looks to them, clon with a short “o” sound. Some even spelled it klon. To correct this mispronunciation, the spelling “clone” came into use: this most native speakers of English will intuitively pronounce with a long “o” sound. As far as I know, the name of the USDA employee who came up with the idea to use the word clone is not recorded, although its first use in a publication is known (but the author of that paper is not the person who came up with the idea of using the word). Now, back to the meaning of the word. First of all, in the sense intended by the early uses of the word, it referred to the group which arises when a plant is asexually propagated. The clone was the group, not the separately propagated elements which made up the group. Note that in contemporary street talk (and, sad to say, much scientific discussion) the elements which make up a clone in the original sense are themselves referred to as “clones”.

This metonymy in meaning is only a part of the problem. Genetics as a science barely existed when the word clone was coined for use in plant sciences. Once genetics began to gain some steam, another blunder was perpetrated: the geneticists insisted that the elements which make up a clone must be genetically identical. Although this flew in the face of centuries of empirical observation of plants subjected to extensive vegetative propagation (for instance, the nineteenth century tulip variety 'Murillo' was the source of dozens of successful commercial entities, all derived by vegetative propagation of one original seedling), the new science prevailed. It wasn't long before the standard belief was that the elements of a clone (in the original sense of the group) were identical. Traditional geneticists seemed to ignore the abundant evidence provided by the variations seen in plants long propagated as clones such as grapes, tulips and apples, just to name a few.

A new field of research called epigenetics attempts to explain some of these effects.

Thursday, October 28, 2010 |

Agli inizi del XX secolo nacque una rosa dal seme di una wichurana grazie a un provetto ibridatore, uno dei primi a usare questa rosa allora relativamente nuova. La giovane pianta crebbe e si fece notare per le sue eccellenti qualità. Fu ben presto commercializzata con il nome del suo ibridatore, Rosa ‘Dr. W. Van Fleet'. Un rosaio piuttosto grande con un'unica ma copiosa fioritura rosa argentato dal profumo di mela verde, caratteristico di molti ibridi di wichurana.

La Rosa ‘Dr. Van Fleet' ebbe grande successo e presto venne ampiamente riprodotta nei vivai.

Fu verso la fine degli anni Venti che in un vivaio alcune di queste rose cominciarono a mostrare una sorprendente e magnifica caratteristica: rifiorivano per tutta l'estate. I rami rifiorenti furono a loro volta riprodotti e quando fu evidente che la rifiorenza era una qualità stabile, alla rosa fu dato un nuovo nome: 'New Dawn'. Fu presentata nel 1930 e si distinse come la prima rosa a essere brevettata negli Stati Uniti. Tutt'oggi la 'New Dawn' è universalmente molto apprezzata.

Nel contesto di questa disamina si prenda nota che la 'New Dawn' è il frutto di quella prima piantina nata dal seme di una wichurana .

La 'New Dawn' divenne anche più popolare della 'Dr. W. Van Fleet' e fu anch'essa intensivamente moltiplicata per via vegetativa. Negli anni Trenta del secolo scorso l'occhio acuto di un rosaista ceco notò che una di queste sue rose produceva rami con fiori stradoppi, con più petali rispetto a quelli della classica 'New Dawn'. E anche questi rami furono riprodotti vegetativamente. Quando divenne evidente che i fiori stradoppi erano una caratteristica stabilizzata, la rosa nata da queste talee fu chiamata ‘Awakening' in inglese, ‘Probuzeni' in ceco (entrambi i termini in italiano significano ‘risveglio').

Le tre rose ‘Dr. Van Fleet', ‘New Dawn' e ‘Awakening' costituiscono un unico clone variante di Rosa wichurana. Forse ci si chiede come questo possa essere, stante che esse non sono esattamente eguali mentre i cloni sono esattamente eguali, per lo meno è ciò che il termine ‘clone' significa, o così la maggior parte della gente ritiene che significhi.

Le cose non stanno così. Il termine ‘clone' (nel senso scientifico in riferimento a una pianta) fu usato per la prima volta negli uffici del Dipartimento di Agricoltura USA. Uno dei ricercatori stava cercando un termine che descrivesse il gruppo (il gruppo, appunto, non le piante separate) che si ottiene quando una pianta viene moltiplicata per via vegetativa. Uno dei suoi colleghi che conosceva il greco antico suggerì di usare il termine greco di ‘ramo'. Nella translitterazione dall'alfabeto greco a quello latino, il termine risulterebbe 'clon'. Per quelli che sapevano il greco antico era chiaro che la 'o' era 'lunga', ma quella grafia confliggeva con l'ortografia inglese, tanto che la maggior parte degli anglofoni pronunciavano la parola come se fosse scritto 'clon' e alcuni anzi scrivevano 'klon'. Per evitare questa pronuncia sbagliata si iniziò a usare il termine 'clone' che un anglofono intuitivamente pronuncia con una 'o' lunga (la stessa differenza di pronuncia che c'è tra ton e tone,, ndt.).

Non pare sia giunto sino a noi il nome dell'impiegato dell'USDA che ebbe l'idea di usare il termine 'clone', e che comunque non è l'autore della pubblicazione in cui il termine apparve per la prima volta.

Ora torniamo al significato della parola. Innanzi tutto, nel senso inteso dai primi usi del termine, esso si riferiva al gruppo nato da una pianta propagata vegetativamente. Il clone era il gruppo, non i singoli elementi propagati separatamente che costituivano il gruppo. E' da sottolineare che nel parlare comune (e triste a dirsi, anche in molte pubblicazioni scientifiche) gli elementi che costituiscono un clone nel senso originario sono loro stessi definiti 'cloni'.

Questa metonimia nel significato è solamente una parte del problema. La genetica come scienza era ai primi vagiti quando fu coniato il termine 'clone' nel campo delle scienze naturali. Quando la genetica cominciò ad affermarsi, si commise un altro svarione: i genetisti stabilirono che gli elementi che formano un clone devono essere geneticamente identici. La nuova scienza prevalse, anche se fu uno schiaffo a secoli di osservazione empirica di piante sottoposte a propagazione intensiva per via vegetativa (per esempio la varietà 'Murillo' del tulipano del XIX secolo fu all'origine di dozzine di varietà differenti, di grande successo commerciale, tutte ottenute per via vegetativa della piantina madre) . Non ci volle molto tempo prima che fosse normale convinzione che gli elementi di un clone (nel senso originario di gruppo) dovessero essere identici. I genetisti tradizionali sembrarono ignorare l'ampia evidenza fornita dalle variazioni viste in piante a lungo propagate come cloni, quali uve, tulipani e mele, solo per citarne alcune. Un nuovo campo di ricerca, l'epigenetica, tenta di spiegare alcuni di questi effetti.

|